wp-pagenavi domain was triggered too early. This is usually an indicator for some code in the plugin or theme running too early. Translations should be loaded at the init action or later. Please see Debugging in WordPress for more information. (This message was added in version 6.7.0.) in /home/mitrades/public_html/wp-includes/functions.php on line 6114wordpress-seo domain was triggered too early. This is usually an indicator for some code in the plugin or theme running too early. Translations should be loaded at the init action or later. Please see Debugging in WordPress for more information. (This message was added in version 6.7.0.) in /home/mitrades/public_html/wp-includes/functions.php on line 6114A Case Study of How Culture and Climate Determined Vernacular Architecture

“We must begin by taking note of the countries and climates in which homes are to be built if our designs for them are to be correct. One type of house seems appropriate for Egypt, another for Spain... One is still different for Rome... It is obvious that design for homes ought to conform to diversities of climate.”

The history of Shikarpur city dates to 1599 when Sind was annexed to the Mughal Empire. The present city outskirts used to be hunting fields or Shikargahs which merged with Sibi, Balochistan during the rule of Emperor Jalaluddin Muhammad Akbar (1556-1605).

Shikarpur came to be known as the ‘Paris of Sindh’ for its rich culture and socio-economic norms, rendering it quite distinct from the other cities of the province.

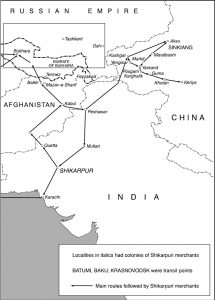

Its good fortune was to be located on an ancient trade route between Afghanistan and India. Indeed, historians claim that the merchant network of Shikarpur extended from southeast Iran to eastern Kashgaria to Turkestan to Arabia. As a result, this glorious city was always a trading hub connected to a consolidated network of Central Asian countries via the Bolan Pass.

By the mid-18th Century, Hindu merchants from all over India were encouraged under Afghan patronage to bring in their networks of commerce and usury and settle here to develop it as a hometown. As the city did not have its own manufacturing, it became known instead for its Hindu bankers and money dealers.

The passage of caravans through it strengthened links to the rest of the world, securing its importance in the region. The extent of the goodwill was such that even a “promissory note” from Shikarpur was acceptable in Central Asian countries on the exchange of goods instead of money.

Just as with the Medici’s of Florence, the Hindus of Shikarpur grew to patronize the city and informed it with their ideas and wealth. In addition to a thriving arts and culture scene, Shikarpur also became home to one of the first three educational institutions of Sindh: CNS Government College Shikarpur. (The others were DJ Science College in Karachi and DG National College in Hyderabad.) CNS was also involved in a great deal of charity work for the city. Cross-cultural trade and travel also brought new knowledge, ideas and notions to Shikarpur, especially when its locals returned from their travels to countries in Central Asia, the Far East, Middle East and Europe.

In addition to attracting Hindu merchants, Shikarpur also became a station for powerful Muslim and Afghan landowners, who had a stronghold on the working middle class. The confluence of such a multicultural and multi-ethnic community distinguished Shikarpur as a rare urban center in Sindh unlike any other contemporary city of that time. It became known as the only place in the subcontinent where complete communal harmony prevailed. This was symbolized by people such as Bhagat Kanwar Ram, a Sufi singer, who gave in charity to both Hindus and Muslims. The Bhaibands, or Sindhi Hindus, were settled in a large number in the city, and all of them were followers of Jhulelal (6), who was influenced by Guru Nanak. (This explains why much of Shikarpur’s wood carvings and paintings on glass depict the founder of Sikhism.) The culture of coexistence remained strong through the ages, so much so that even during the challenging time of the partition of India and Pakistan riots broke out in the entire region except for Shikarpur.

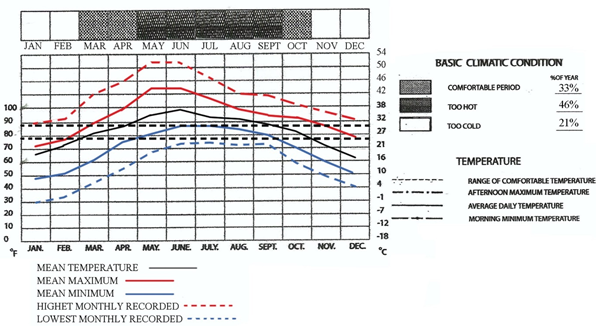

The city of Shikarpur sits in the tropical climatic zone; the summers in this region are harsh and arid with a remarkable absence of air currents during the inundation season. The hot weather starts in April and ends in October and is generally ushered in by violent gusty winds. The average temperature goes up to 45 degrees Centigrade in June, which is the hottest month in Shikarpur. The winters are usually mild and temperatures fluctuate between day and night, but occasionally there are extreme winter days due to Siberian winds from the north. Therefore, in the winter months, there are some chilly spells. The humidity is below the comfort range most of the year.

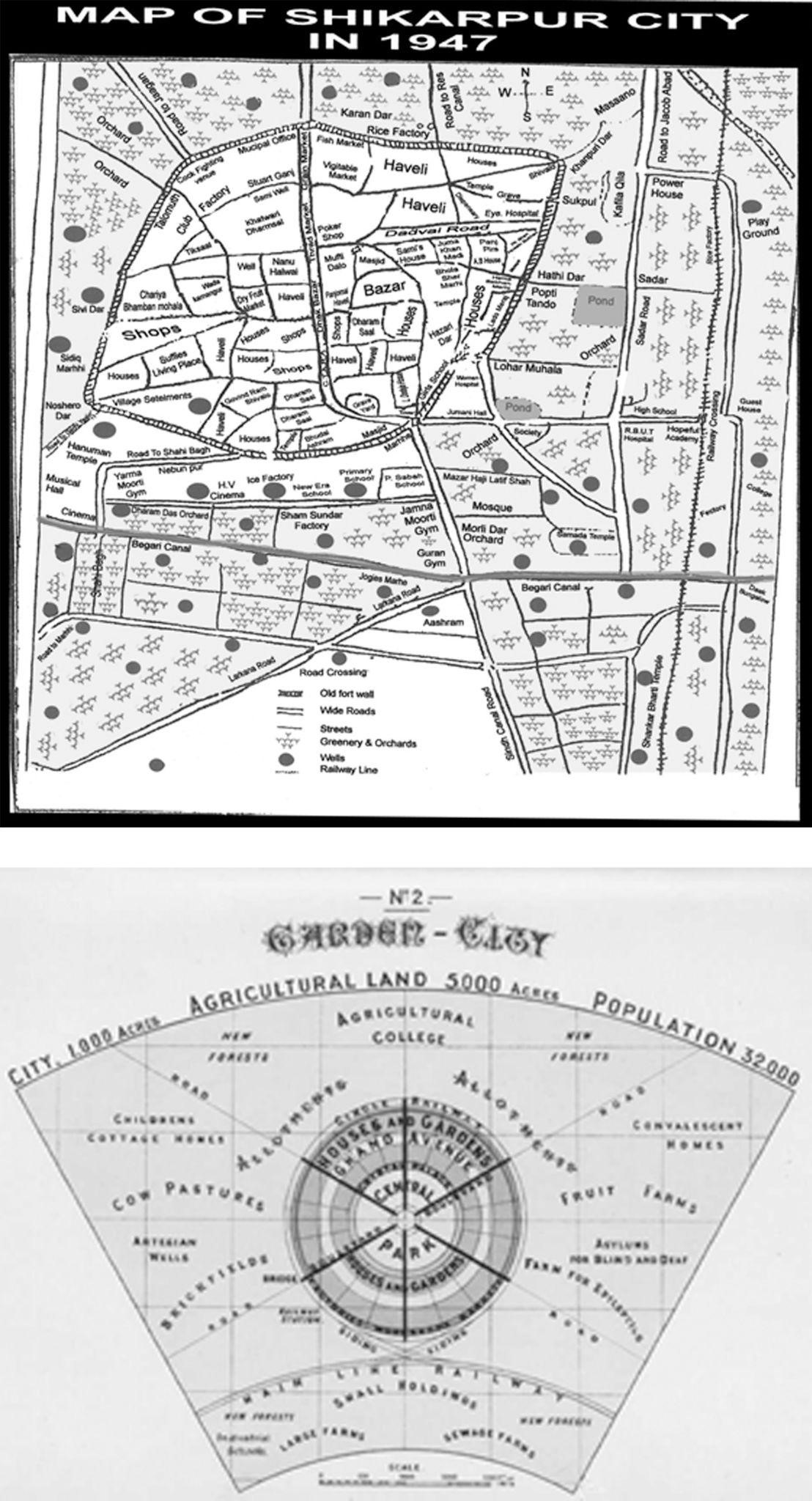

Historically, the hunting fields or Shikargahs, which would become Shikarpur, were surrounded by orchards of mangoes—the pickling and not the sweet kind. In the evenings, people were drawn to these gardens for Sufi music events and also rich Hindus would give gold coins to these performers. People also came to cool off, as the orchards and gardens helped maintain a moderate climate. And so, Shikarpur had elements of the garden city akin to the concept of Ebenezer Howard (refer to figure 3). Shikarpur is also known for the sweet water through these garden canals which also charge the city’s tube-wells.

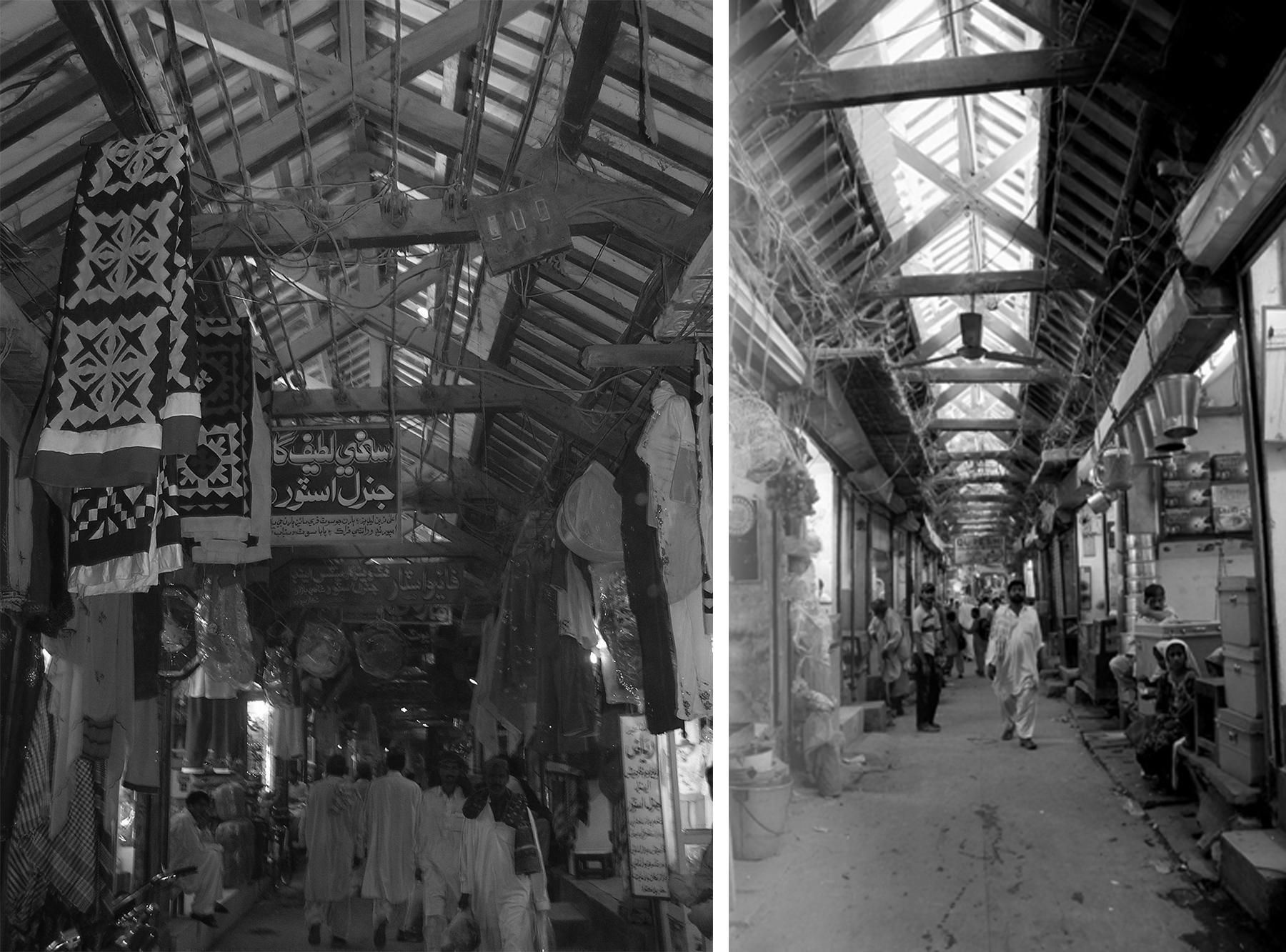

Shikarpur was originally laid out as a walled city built with burnt brick, enclosing a space of 3,800 yards in circumference with eight gated entry points. The spatial planning of its historic core retains the original labyrinthine, morphological pattern of narrow, winding streets and alleys. The inner streets are wide enough to accommodate only pedestrian or light vehicular traffic. The historic city is made up mainly of residential fabric, except for the bazaar street that cuts across the center, along the north-south axis.

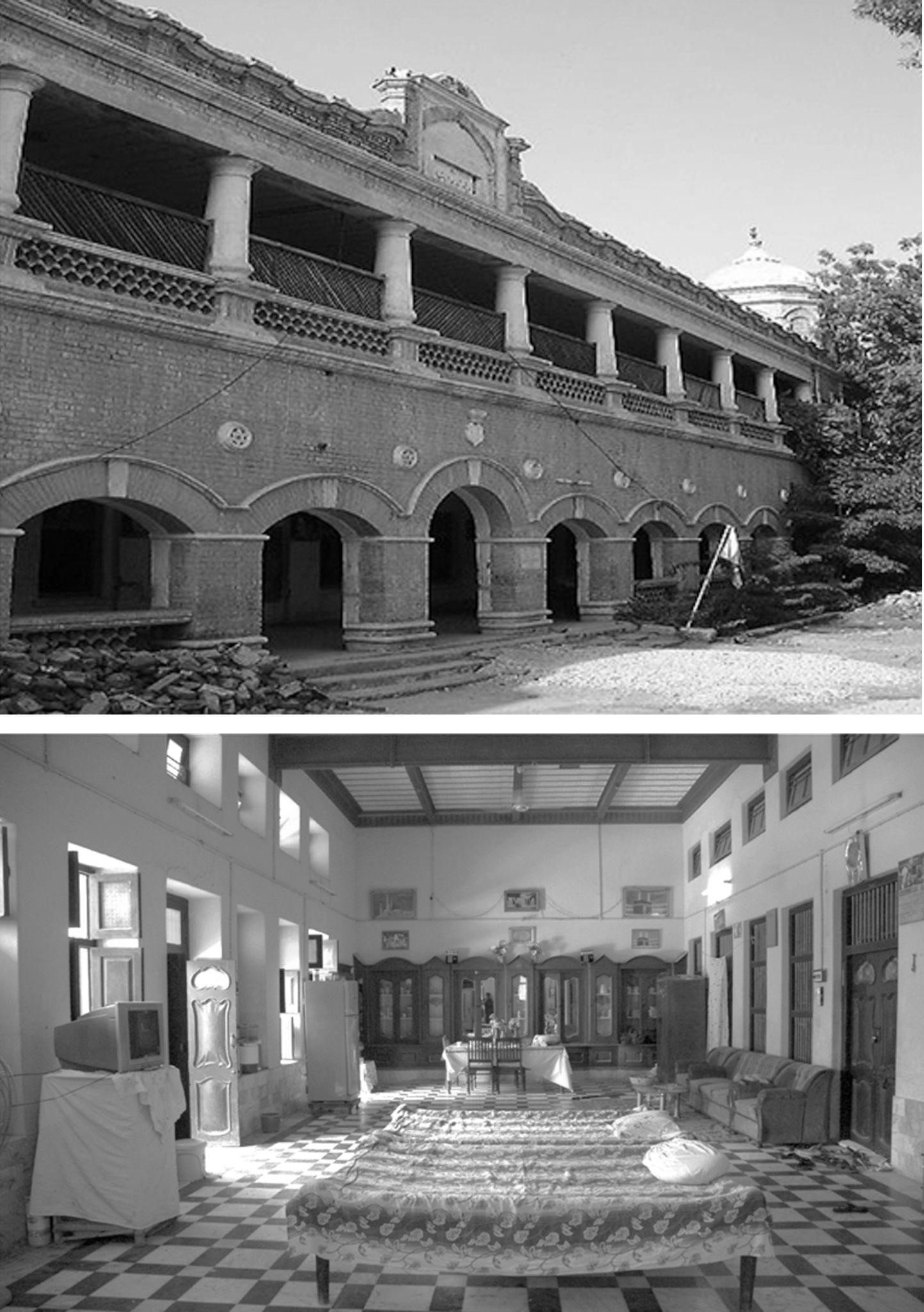

Buildings, like music, art and rituals, apprehend culture and the most distinctive characteristic of Shikarpur’s built fabric is its Havelis, which emerged as a response to the culture of commerce. The city’s merchants were often away on their travels and thus, their families ended up frequently living alone. In order to ensure the security of their families, these merchants devised a system in which 10 to 20 houses were built on a single plot in two rows divided by a lane and surrounded by high walls. This courtyard-style arrangement was called a haveli.

A communal haveli has a single big entrance door, mostly opened and closed at specific timings by the inhabitants. The houses inside were independent but had privacy, (the only reason their walls were attached was to avoid exposure to the sun and hence keep cool). This architecture also supported the values of nukh or kinship which gave preference to roots over caste.

The residential unit of the haveli became a symbol of pride for the merchants of Shikarpur, who employed master craftsmen to embellish their houses, especially during the latter part of the 19th Century. This architecture became the hallmark of the city.

Mostly the Havelis had one spacious room known as a dalo or living hall with two rooms set behind it. A similar kind of layout was adopted for the first floor also. (8) The high ceilings permitted the rooms to have large windows that allowed the air to stratify. Walls with small windows at the top were used to flush out the warm air.

These rich patrons of architecture and art were slowly replaced by refugees or settlers who lacked the same financial means and personal association with the city. As a result, the architectural fabric started to crumble in a decay that continues to date. The built heritage has not been protected. The historic Havelis have been demolished and the arrival of abundant cheap fossil fuels gave rise to mechanical systems for environmental control.

And so, the climate was no longer a key determinant for Shikarpur’s architecture and master planning as for the rest of the world. Technically, one could build a glass skyscraper in the middle of this extreme desert heat and still be humanly comfortable with air-conditioning. This is, as a global shift in thinking espouses, however, not the sustainable way of approaching urban living. We are increasingly attempting to go back to the wiser ways of our forefathers who made buildings that provided human comfort. Theirs was a passive approach to creating sustainable architecture unlike the modern unprecedented use of non-renewable energy that has contributed to global warming and a deterioration of the urban environment.

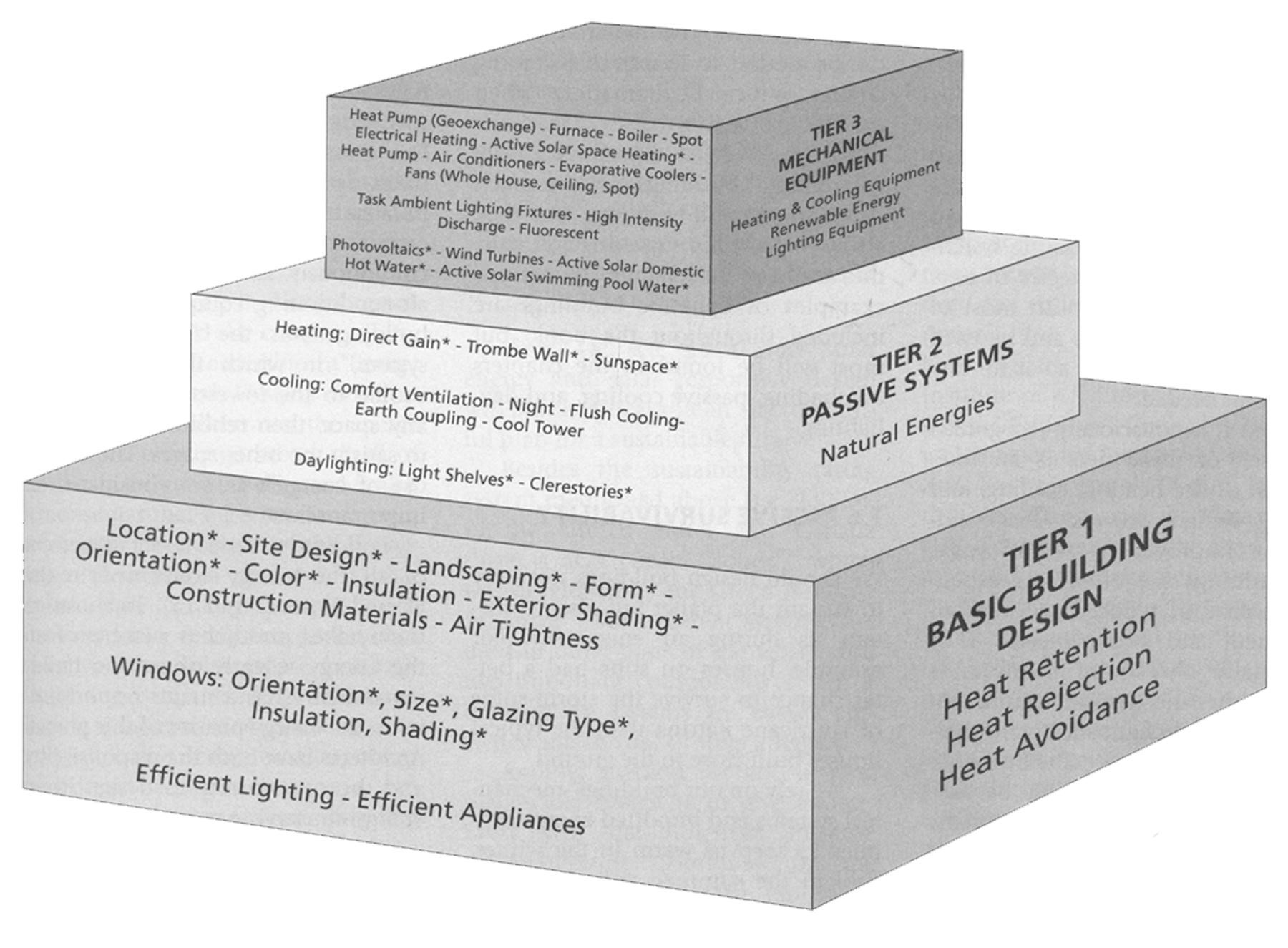

When we talk about a passive approach to creating sustainable architecture to provide human comfort, we need to define both thermal comfort and sustainable development. ASHRAE Standard 55-66 defines thermal comfort as that condition of mind which expresses satisfaction with the thermal environment. (9) The United Nations World Commission on Environment and Development defines sustainable development as: "development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” (10) If we go by the principles laid down by Norbert Lechner, the author of extremely influential ‘Heating, Cooling, Lighting: Sustainable Design Methods for Architects’ we need to take a three-tier approach.

This is the approach we should take to sustainable architecture. Lechner’s principles should be used to evaluate design strategies that are used in the vernacular architecture of Sindh where the summers are hot and dry and the winters cool and dry with a major temperature swing between day and night.

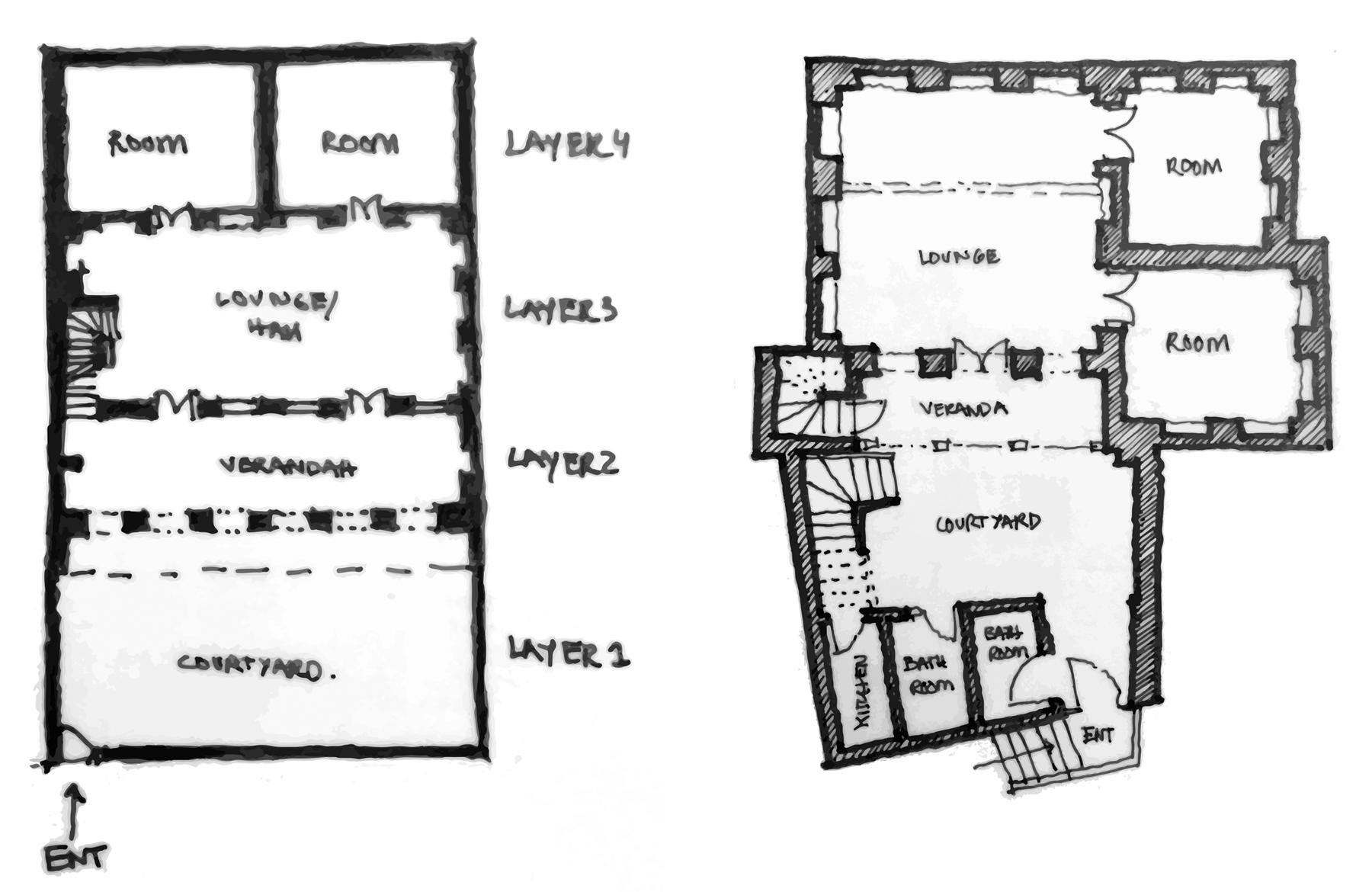

In present times, Architects need to consider the design of the building while keeping in mind Lechner’s concept of sustainable architecture. This involves a three-tier approach to understand the living spaces of Shikarpur, which are designed in multiple layers. Each layer filters the level of privacy and these layers also respond to climatic conditions.

The first layer is open to the public and is open to the sky. During the summers this space is usually used for communal gathering (katchehri) in the early mornings or late evenings. During winter, the open courtyard space is used for the same purpose and to soak up the winter sun. During the late evening or night in the winter, this space is enjoyed with a bonfire.

The second layer is a veranda. This is a semi-open space looking out to the first open layer. This is where the level of privacy starts to increase. The third layer is the living room after the veranda, which is the double-height center space that acts as a living room. This space acts as a communal gathering in the hot summers.

The last layer is the bedroom, which is oriented to the north side of the building façade and is thus, exposed to less sun in the summer.

The residential planning is composed of row houses; therefore, they share walls with the adjacent dwelling.

The climate design priorities are:

Unlike with Shikarpur’s extremely hot summers, winters were a low design priority for the city’s vernacular architecture, although it is still important to address.

Conclusion

Hence Shikarpur - once a Paris of Sindh and proved to be the trade link between Central Asia to Subcontinent – was virtually the nexus of commerce in the region. The rich influence traders bought ideas from wherever they traveled into art and architecture to their context, prevailing climate and affluent culture at that time. This resulted in a unique living environment with the concept of Haveli houses with large courtyards, which were used both in winters for a bonfire and in summers the resident enjoyed the cooler breeze. This unique architectural language was inspired by the climate of the region and the culture of the Shikarpur city. With the understanding of modern sustainable architecture principles of Norbert Lechner, the architectural language of Shikarpur city suggests that in their time they emphasized the building design on passive means rather than in modern times we are more dependent on the mechanical system, with the help of abundant fossil fuels which is not sustainable for our future generation.

Many other events in the history of the region have affected the built fabric of the city, main the partition of the subcontinent where it led to the migration of thousands of refugees from both sides and those post-partition inhabitants of the Shikarpur city hasn’t been able to sustain the cultural values of the city through time and therefore today the city lies at the mercy of a pity.